Roasting the Planet: Inside Big Meat and Dairy’s Climate Reckoning

- Industry News

- Oct 20, 2025

- 4 min read

The corporations feeding the world are also roasting the planet. A new global report, Roasting the Planet: Big Meat and Dairy’s Big Emissions, lays bare the colossal climate footprint of industrial livestock, and the growing risks it poses not just to ecosystems, but to the food industry’s own long-term viability.

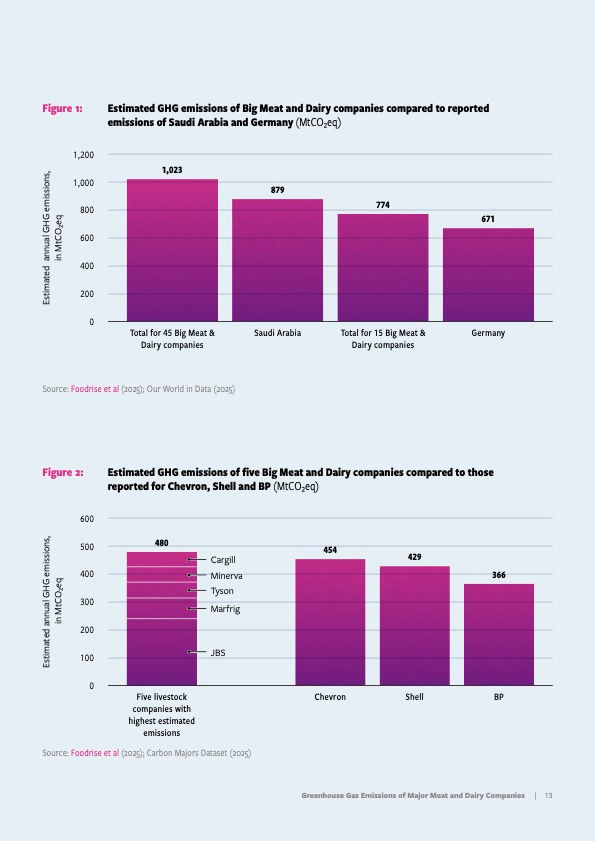

Co-authored by Foodrise, Friends of the Earth U.S., Greenpeace Nordic, and the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy, the study calculates that just 45 of the world’s largest meat and dairy companies emitted 1.02 billion tonnes of greenhouse gases in 2023. That’s more than Saudi Arabia, and if grouped together, these firms would rank as the ninth-largest emitter globally.

The top five, JBS, Marfrig, Tyson, Minerva, and Cargill, were responsible for nearly half of the total, pumping out more greenhouse gases than Chevron, Shell, or BP. Their methane emissions alone exceeded those of all 27 EU member states and the UK combined.

The findings, though shocking, are consistent with a trend climate scientists have warned about for years: without tackling livestock emissions, the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C target is effectively unreachable.

The Other Oil Industry

Industrial meat and dairy are now the new “carbon majors.” The sector’s emissions trajectory and political behavior mirror fossil fuels, from funding climate denial and lobbying against regulation, to marketing “net zero” aspirations with no credible roadmap to get there.

The report documents how major producers like JBS have used misleading climate pledges and greenwashed advertising campaigns to delay systemic change. The Brazilian meat giant, which slaughters more than 20 million cattle and 3.6 billion chickens each year, had previously claimed it would reach net zero by 2040. Earlier this year, it walked back that target, saying it was “never a promise.”

Such double-speak, says Oxford University professor Paul Behrens in the report’s foreword, reflects an industry “deeply unserious about the planet’s future livability.” He adds, “Aspirations don’t help anyone in a 40°C heatwave. Aspirations are not going to keep this planet from being unlivable for billions of people.”

Behind the marketing, the business model remains built on expansion. JBS projects a 70% increase in global animal protein demand by 2050. Tyson Foods forecasts almost 95 billion more pounds of beef, pork, and chicken production in the coming decade. The result: mounting emissions, deforestation, and ecological strain, even as consumer and investor pressure for sustainable alternatives intensifies.

A Transparency and Accountability Crisis

The report’s authors note that emissions data from Big Meat and Dairy remain opaque and inconsistent. Most companies do not fully disclose their supply-chain (Scope 3) emissions, which make up the vast majority of their footprint. Those that do often use intensity-based metrics that conceal the effect of rising production volumes.

The result is a major blind spot in both corporate climate accounting and national emissions inventories. Industrial livestock operations are still treated as agricultural exceptions rather than energy-scale emitters.

Worse, industry groups are pushing governments to adopt the GWP* metric, a controversial system that downplays methane’s short-term heating effect. By shifting focus to “no additional warming” rather than absolute emissions cuts, it risks giving the illusion of progress while allowing companies to maintain current output. Policymakers in New Zealand and Ireland are among those considering this approach under pressure from agribusiness lobbies.

From Fossil Fuels to Food Systems

The report makes clear that cutting fossil fuels alone is no longer enough. Animal agriculture already contributes 12% to 19% of all human-caused greenhouse gas emissions, largely from cattle-related methane and nitrous oxide. Without intervention, “business-as-usual” production is projected to add another 0.3°C of global warming by 2050.

That’s where food system transformation comes in. Researchers highlight that 83% of global meat production and 77% of consumption occur in high- and upper-middle-income countries, while low-income nations account for just 2%. A dietary shift in wealthy countries could deliver the single biggest emissions reduction available to the global food system.

Transitioning to the EAT-Lancet Planetary Health Diet, a predominantly plant-rich diet with limited animal products—could cut food-related emissions by 61%, free up farmland the size of the EU, and, if rewilded, draw down the equivalent of 14 years of global agricultural emissions.

As Shefali Sharma of Greenpeace Germany puts it, “Farms that restore nature and communities, not corporate-controlled factories, should be at the center of our food system. It’s not too late for governments to commit to such a transition in their climate plans coming out of this COP.”

The Economics of a Just Transition

The report’s recommendations target not only environmental sustainability but also economic resilience. A sector this large cannot be transformed by consumer choice alone. It requires policy alignment, financial reform, and a just transition framework that supports farmers and rural workers through the shift.

The authors urge governments to:

Mandate full emissions disclosure for meat and dairy companies, broken down by gas and production type.

Set binding national reduction targets, including separate methane goals.

Enforce the “polluter pays” principle, ensuring environmental and social costs are internalized.

Redirect subsidies and public procurement toward agroecological and plant-based systems.

Divest public and multilateral funds from major livestock corporations and reinvest in low-carbon food solutions.

Such measures, they argue, would level the playing field for innovators in alternative proteins, regenerative agriculture, and circular food systems, while helping nations meet their climate commitments.

A Fork in the Road

The title Roasting the Planet is more than a metaphor. As floods, droughts, and heatwaves devastate farms across continents, the livestock industry faces an existential paradox: it is both a victim and a driver of the climate crisis.

In Australia, more than 140,000 farm animals were lost in floods this year; in Europe, heat stress is slashing dairy yields; in Latin America, deforestation linked to beef and soy continues to fuel both biodiversity loss and global emissions. Yet many of the same companies expanding in these regions are also seeking new markets in Asia and Africa under the banner of “feeding the world.”

The science is unambiguous, the economics increasingly compelling. As Behrens concludes, “The sector that feeds humanity has the power to become its savior rather than its destroyer.”

Whether policymakers, investors, and consumers will demand that transformation, or allow the planet to keep roasting, will define not just the future of food, but the future of life itself.

Comments